Ben’s filming commitment at Waiouru army base required us to make an early start. As daylight dawned the hills of Wellington were shrouded in mist. The night before we had seen a sea mist creeping in from the south. This morning it had spread further inland and we were facing fog as we headed north on State Highway 1. By the time we reached the Kapiti coast we were in brilliant sunshine and the bank of fog could be seen just sitting off shore to the west.

Continuing north we crossed the Foxton Flats dispelling my belief that the whole of New Zealand was hilly or mountainous. It is a flat coastal plain of agricultural land. Having crossed the flats the hills reappeared and the landscape became more interesting. Here, the land had a much more parched look about it than that around Wellington. The grass was golden brown and wind blown.

We passed through a couple of small towns, Bulls being the first with lots of references to bulls. The antique shop is called Memorabull, the police station constabull and the town is referred as unforgetabull. The next town was Taihape renowned for wellingtons and corrugated iron, including a giant multicoloured welly made out of corrugated iron. Other corrugated sculptures decorate the town. Also in the town, at the side of the road is an old twin engine plane mounted on a plinth. Steps lead up and into it where you can have a drink and a bite to eat.

As we approached Waiouru the impressive volcanic peak of Ruapehu (2797m) came into view with patches of snow filling the gullies surrounding the summit. At Waiouru I deposited Ben at the army camp for his assignment and went to explore the region beyond, a volcanic desert area of stubby vegetation dominated by the conical peak of Mt. Ngauruhoe (2291m). Where water has created a course through this land you can see the layers of deposited volcanic material from numerous eruptions. I discovered the start of the Northern Circuit trail and took advantage of the photographic opportunities in glorious weather.

The whole of this area is restricted as it is an army training area. Ben was here to film tanks firing at a target and expected it to take a couple of hours but not everything went to plan. As I drove back to Waiouru expecting him soon to be finished I saw him filming with several tanks around him. Unfortunately, the firing started a fire in the dry shrubs near the target so that delayed things and his expected two hours work turned into five.

This gave me time to drive to Ohakune to take possession of our accommodation for the night. On the way I stopped at the Tangiwai Memorial. On Christmas Eve, 1953, an express train was travelling from Wellington to Auckland full of passengers looking forward to Christmas. High on the slopes of Ruapehu a moraine holding back a glacial lake collapsed. A six metre wall of water and debris came hurtling down the river bed. At Tangiwai the railway crosses the river on a bridge. The wall of water came down with such force that the bridge was destroyed as well as the road bridge nearby and three other bridges. Being a remote area nobody witnessed the catastrophic effects of the deluge. By the time they knew, it was too late to warn the train. Despite the fact that it was travelling at a relatively sedate 40mph, the engine plunged into the gaping hole where the bridge had been, hitting the bank on the far side. The first six coaches followed. The seventh teetered on the edge before joining the other six. 151 people were killed and Christmas was ruined for a great many people.

Throughout our travels around North Island there is one plant that has caught my eye. It is like a pampas grass with long storks with golden seed heads fluttering in the breeze. There are whole hillsides of them in places. There were lots if them close to the Tangiwai Memorial and they looked spectacular in the brilliant sunshine against the background of the clear blue sky.

Throughout our travels around North Island there is one plant that has caught my eye. It is like a pampas grass with long storks with golden seed heads fluttering in the breeze. There are whole hillsides of them in places. There were lots if them close to the Tangiwai Memorial and they looked spectacular in the brilliant sunshine against the background of the clear blue sky.

I soon found The Hobbit Motor Lodge, so named because the area was used as a setting for filming, a claim many areas of New Zealand can boast about. Ohakune is a small ski resort village catering for the skiers who venture on to the southern ski slopes of Ruapehu.

Eventually the call came from Ben that he had finished so I returned to Waiouru to pick him up. It was exceptionally hot with no breeze. The temperature was 31C. If it is going to be like this when we do the Tongariro Crossing we are going to find it very uncomfortable. We drove past the Hobbit Lodge and continued up the hill through forest and on to the lava strewn upper slopes where the skiing takes place during the southern winter. Looking at the landscape, more akin to a quarry. on this hot, sunny afternoon it is hard to believe that this whole area is covered sufficiently to allow skiing.

Returning to the forest we stretched our legs on a walk to Waitonga Falls, which took us through the forest, across an area of marshland and back into the forest and down to the waterfall. As a spectacle it was a let down as very little water tumbled over the 50m cliff.

Returning to the forest we stretched our legs on a walk to Waitonga Falls, which took us through the forest, across an area of marshland and back into the forest and down to the waterfall. As a spectacle it was a let down as very little water tumbled over the 50m cliff.

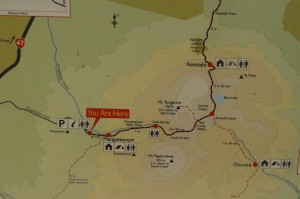

When doing the Tongariro Crossing you have to plan your logistics beforehand. There are several shuttle services which can either return you to your car or hotel. We had to get up early to take our car to Ketehahi, where we were finishing, to pick up the shuttle to take us round to the start at Mangateporo. As we drove back and forth the mountains were shrouded in early morning mist but we knew that as soon as the sun came up it would quickly burn away giving us a glorious day and fantastic views, even if it might prove a little warm.

The two ends of the walk were busy, particularly the more popular Mangateporo starting point, where our Maori shuttle driver performed a ritual prayer to help us on our way.

The two ends of the walk were busy, particularly the more popular Mangateporo starting point, where our Maori shuttle driver performed a ritual prayer to help us on our way.

From Mangateporo the path climbs gently and we covered the first 4km to Soda Springs at a reasonable pace. The path throughout much of the route is very much a manufactured path with long stretches of small compacted stones supported by wooden boards on either side. Steps help with the climbs and occasionally board walks have been erected. The purpose of this is to encourage people not to wander off the path and endanger the fragile environment either side of it. It was just after eight when we started walking and already it was hot. There was no breeze but at least the cloud around the peaks was lifting. The track was crowded with a constant stream of walkers, mostly young, who largely seemed to be in a hurry. Funnily enough, although we were going at a steadier pace we kept seeing the same people as they kept having to take more rests.

From Soda Springs the path climbs more steeply up to the rim of a large crater. Thankfully there was a slight breeze which took the edge off the temperature and made the effort a little more bearable. To our right, rising very steeply out of the edge of the crater was the dramatic cone of Ngauruhoe. From here we could take a detour and climb to the summit but it was very steep and would have added at least three hours to our day. As we already had plans to take the detour to the summit of Mt. Tongariro, we declined this option. Had we taken it we would certainly have lost the crowds.

From Soda Springs the path climbs more steeply up to the rim of a large crater. Thankfully there was a slight breeze which took the edge off the temperature and made the effort a little more bearable. To our right, rising very steeply out of the edge of the crater was the dramatic cone of Ngauruhoe. From here we could take a detour and climb to the summit but it was very steep and would have added at least three hours to our day. As we already had plans to take the detour to the summit of Mt. Tongariro, we declined this option. Had we taken it we would certainly have lost the crowds.

Crossing the flat expanse of the crater we reached the climb up the rim on the other side. This was taking us towards the Red Crater but before we reached it we turned north and followed an undulating ridge round to the summit of Tongariro. Every so often we got really strong smells of sulphur but could not see where it was coming from. Occasionally the smell was so strong we could taste it. Using binoculars to scan all around we saw, just to the side of an emerald coloured lake a few whisps of steam. The colours of this relatively young rock on the ridge were vivid with yellows, oranges and reds among the more usual colours.

Crossing the flat expanse of the crater we reached the climb up the rim on the other side. This was taking us towards the Red Crater but before we reached it we turned north and followed an undulating ridge round to the summit of Tongariro. Every so often we got really strong smells of sulphur but could not see where it was coming from. Occasionally the smell was so strong we could taste it. Using binoculars to scan all around we saw, just to the side of an emerald coloured lake a few whisps of steam. The colours of this relatively young rock on the ridge were vivid with yellows, oranges and reds among the more usual colours.

Pillars of rock pierced the air where they had been forced out by enormous pressure and solidifying before they could topple. As we looked down the numbers below, resting and admiring the Red Crater were beginning to thin out. In the distance clouds were rising above a distant ridge as if from a volcano but neither of us believed this to be what was actually happening. As there were clouds all around us, gradually getting closer, we felt sure these were thermal clouds created by rising air currents. They looked authentic though.

Pillars of rock pierced the air where they had been forced out by enormous pressure and solidifying before they could topple. As we looked down the numbers below, resting and admiring the Red Crater were beginning to thin out. In the distance clouds were rising above a distant ridge as if from a volcano but neither of us believed this to be what was actually happening. As there were clouds all around us, gradually getting closer, we felt sure these were thermal clouds created by rising air currents. They looked authentic though.

Returning by the same route we dropped down to the Red Crater, a truly spectacular chasm of dark red rock. There, in the middle of the crater was the vent from which everything had spewed when it last erupted. Fantastic!!

Returning by the same route we dropped down to the Red Crater, a truly spectacular chasm of dark red rock. There, in the middle of the crater was the vent from which everything had spewed when it last erupted. Fantastic!!

We had now entered a volcanic hazard zone, an area of possible eruption. While indicators at the start of the walk suggested there was nothing other than natural activity today we had to be prepared and know what to do in the event of an eruption occurring. The source of any possible eruption was a crater called Te Maari. This last erupted in 2012 and the route we were about to take goes to the left of the crater, well within the 3km exclusion zone imposed when an eruption occurs.

Below the Red Crater, at the foot of a steep scree slope nestled some emerald green lakes, known, as you would expect, as the Emerald Lakes. These were stunning and the larger of the three was still encouraging quite a lot of people to congregate around and enjoy. Again we ventured slightly off track and went to investigate some steaming vents to one side of one of the lakes. Naturally, here the sulphur smell was at its strongest.

Below the Red Crater, at the foot of a steep scree slope nestled some emerald green lakes, known, as you would expect, as the Emerald Lakes. These were stunning and the larger of the three was still encouraging quite a lot of people to congregate around and enjoy. Again we ventured slightly off track and went to investigate some steaming vents to one side of one of the lakes. Naturally, here the sulphur smell was at its strongest.

Rejoining the main track we crossed another large, much older crater bed before climbing up to a ridge, Behring which nestled the largest lake on the route, this time the Blue Lake, also appropriately named. From here we began our long descent to the end. Whilst we had covered the first few kilometres quite quickly the area around all the geological sites of interest and the detours had slowed our linear progress which meant we were still only about half way when we began our descent.

Earlier in the day we had noticed cloud rising from a distant ridge believing it to be just that, cloud. As we descended the Te Maari crater came into view with lots of steam rising from it. I had wanted those clouds to be volcanic steam and that is what they turned out to be.

Earlier in the day we had noticed cloud rising from a distant ridge believing it to be just that, cloud. As we descended the Te Maari crater came into view with lots of steam rising from it. I had wanted those clouds to be volcanic steam and that is what they turned out to be.

As we descended it seemed to be getting hotter. We were now walking directly into to the sun and there was no escaping it. We were now having to ration our water, each having started the day with one and a half litres. Temperatures hadn’t quite reached the peak of the previous day, largely because if the slight breeze, but they were now nudging 30C as we descended.

After eight and a half hours we finally reached our car. There were crowds waiting for their shuttle service. Not a pleasant way to end your day, having to wait a long time for your pick up when you are tired and thirsty, particularly when there are no facilities and no possibility of topping up fluid levels. We, on reaching the car, were desperate to top up ours. We also had another worrying priority to deal with. We hardly had any fuel left in the car. Last night the garage had closed and the only other garage we saw this morning hadn’t yet opened when we went past it. Had we got enough to get us to the nearest garage 31km away? According to the gauge we had a range of 48 kilometres left in the tank. That depended on how well I drove. We turned off the air con and opened the windows. Later we closed the windows in case it was causing wind resistance and using up more fuel. What neither of us wanted, after our day’s walking, was to run out of fuel 5 km short of the garage and have to do more walking. We made it with a few kilometres left in the tank and as well as filling the car with fluid, we filled ourselves and felt much better for it.

We then just had a short drive to Whakapapa Village where we were spending a night in a motor lodge attached to Chateau Tongariro, an imposing and totally out of character building. However, they served good beer and steak and if we could have summoned up the energy we might have made use of the spa pool, but instead we took more beer back to our room, watched the rugby and went to bed.

The 19.4km Tongariro Crossing is described not only as New Zealand’s finest walk but one if the world’s. It is certainly incredibly spectacular and you see a lot in a day. If you do decide to do it you really do need to choose a good day if you are to get the most out of it. However, you have to be prepared to share the experience with lots of other people, mostly young, who probably want to go faster than you. The crowds do mean that when you get bored of looking at attractive geological features there are plenty of other attractive features to sustain your interest and take your mind off the effort!