The plane touched down at Tan Son Nhat International Airport during the evening, with the city illuminated in the distance. Having collected our luggage, we emerged into the busy concourse of Arrivals to be met by Da Lat, our guide for this section of our trip. As we drove towards the city Da Lat talked to us about Ho Chi Minh City, giving us a little background information. His English was good but his accent, which was a little clipped, took a while for us to adjust to. He had certain mannerisms which, in an English person might have been annoying but coming from Da Lat was endearing. He started many of his sentences with, ”You know….”

We went straight to the hotel, Au Lac, in the heart of the city, which was heaving with people enjoying the new year festivities. On reaching the hotel, it was difficult to get to the front door through the wall of parked motorcycles on the pavement. Once inside, we checked in and then went about the process of trying to order food from the bar on the roof. Considering we were the only ones eating, it was amazing that it could take 90 minutes for them to produce a pizza. Adjacent to the bar there was an open rooftop pool overshadowed by a very futuristic 68 storey building with a disc sticking out near the top which acted as a helicopter pad. Ho Chi Minh is not like Hanoi or Hue. It is a modern city with tower blocks, multinational firms, McDonald’s, neon lights and an atmosphere of much greater wealth than other cities in Vietnam.

The following morning, long before dawn, I was surprised to be woken by crowing cockrels. I thought they would have disappeared as quickly as the tower blocks replaced the much simpler, older buildings. Then I discovered where the early morning chorus was coming from; below our window was an area that had not yet been bulldozed to make way for the next tower block. It was an example of old Saigon with simple housing, small shacks for shops and enclosed yards where the cockrels lived.

After breakfast we were met by Da Lat and taken to visit remnants of French occupation, Notre Dame Cathedral and the Central Post Office, both fine examples of French architecture. They were adjacent to each other, so the visit was quite simple. It was made simpler by the fact that we were not allowed into the cathedral because it was a Sunday and services were taking place. The square in front of the cathedral was busy, but the square in front of the post office was even busier. And it was no quieter inside. It still functions as a post office but has a lot more inside besides. Designed by Gustave Eiffel it is the epitome of everything French. Back outside, there was a wide range of stalls vying to attract tourists to part with their money. The cards that opened up into very intricate 3D pictures were incredibly complex and beautiful, but I resisted.

It was a place for posers, not just Chinese tourists who have to have their photograph taken in front of every iconic building or monument, but for chic looking people in their best outfits behaving like catwalk models. Slick men sitting on flashy motorcycles, far too powerful for the streets of Saigon. It was a great place for people watching.

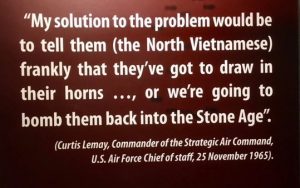

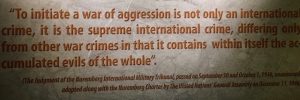

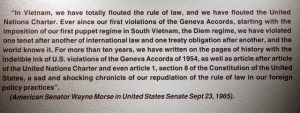

Dragging ourselves away from people watching, we next visited the War Museum. Outside were aircraft and armoured vehicles used by the Americans, but I had no interest in them as they tend to leave me cold. I was more interested in the human impact of the war and the stories of those, on both sides. This proved to be a harrowing, graphic presentation, largely through pictures and words, that really brought home the evils of war. The Vietnam War was really the first war that we remember as we grew up. It was played out on the news, but what we saw then was very much the perspective of the American offensive against the evil communist hordes known as the Viet Cong. While there was evil on both sides, what the Americans did was horrendous. Perhaps the museum can be described as being biased towards the Vietnamese, but many of the pictures and accounts were provided by the Americans.

Dragging ourselves away from people watching, we next visited the War Museum. Outside were aircraft and armoured vehicles used by the Americans, but I had no interest in them as they tend to leave me cold. I was more interested in the human impact of the war and the stories of those, on both sides. This proved to be a harrowing, graphic presentation, largely through pictures and words, that really brought home the evils of war. The Vietnam War was really the first war that we remember as we grew up. It was played out on the news, but what we saw then was very much the perspective of the American offensive against the evil communist hordes known as the Viet Cong. While there was evil on both sides, what the Americans did was horrendous. Perhaps the museum can be described as being biased towards the Vietnamese, but many of the pictures and accounts were provided by the Americans.

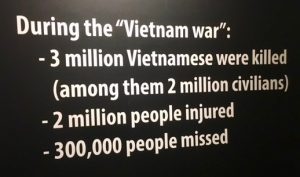

I don’t think the Americans really knew who the enemy were, so they tended to kill indiscriminately and as everybody looked the same, the majority of those killed were, in fact, innocent civilians; they just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Also, we were led to believe that President Diem of South Vietnam, whom the Americans were supporting, was a good and fair president. He was, in fact, a puppet and a despot surrounded by puppets and despots who ordered despicable things to be done to their own people, particularly the Buddhists whom they persecuted.

I don’t think the Americans really knew who the enemy were, so they tended to kill indiscriminately and as everybody looked the same, the majority of those killed were, in fact, innocent civilians; they just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Also, we were led to believe that President Diem of South Vietnam, whom the Americans were supporting, was a good and fair president. He was, in fact, a puppet and a despot surrounded by puppets and despots who ordered despicable things to be done to their own people, particularly the Buddhists whom they persecuted.

There were so many harrowing images, but one in particular stands out. A North Vietnamese had been captured and was being subjected to waterboarding. His head is covered in a sack, and water is being poured on to his face. Holding the prisoner down is a blond American soldier sitting on the victim’s torso. While he is doing this, he is smoking and there is a huge smile across his face. It is hard to believe that one human being could do that to another; it is even harder to believe that it could be enjoyed.

There were so many harrowing images, but one in particular stands out. A North Vietnamese had been captured and was being subjected to waterboarding. His head is covered in a sack, and water is being poured on to his face. Holding the prisoner down is a blond American soldier sitting on the victim’s torso. While he is doing this, he is smoking and there is a huge smile across his face. It is hard to believe that one human being could do that to another; it is even harder to believe that it could be enjoyed.

Another section of the museum focused of the American use of Agent Orange. It was a mixture of toxic herbicides that they used to kill off forests where they believed the North Vietnamese to be hiding, to destroy crops so they could starve the population into submission. In a ten-year period from 1961 to 1971 they sprayed 20,000,000 gallons of it in large areas of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. While the consequences of that were devastating at the time, the legacy continues to do vast amounts of harm. In Vietnam alone, there a two million people who are affected, as it causes cancer, interferes with DNA causing horrendous birth defects, and also causes severe psychological and neurological disorders. But the Americans have not got away with it for those that worked with this deadly agent, and their descendants, are suffering from the same disorders. The photos of disfigurement at birth are the stuff of nightmares.

Another section of the museum focused of the American use of Agent Orange. It was a mixture of toxic herbicides that they used to kill off forests where they believed the North Vietnamese to be hiding, to destroy crops so they could starve the population into submission. In a ten-year period from 1961 to 1971 they sprayed 20,000,000 gallons of it in large areas of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. While the consequences of that were devastating at the time, the legacy continues to do vast amounts of harm. In Vietnam alone, there a two million people who are affected, as it causes cancer, interferes with DNA causing horrendous birth defects, and also causes severe psychological and neurological disorders. But the Americans have not got away with it for those that worked with this deadly agent, and their descendants, are suffering from the same disorders. The photos of disfigurement at birth are the stuff of nightmares.

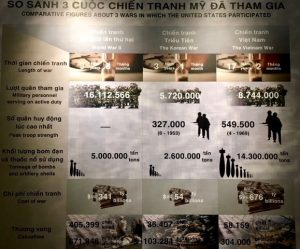

Many of the statistics associated with this war are mind boggling. They dropped more bombs during this war than all the allied forces combined in the Second World War, there are 80,000 unexploded bombs over the border in Laos and every year 300 people are killed and maimed when they accidentally detonate an unexploded device. The nightmare goes on!

Many of the statistics associated with this war are mind boggling. They dropped more bombs during this war than all the allied forces combined in the Second World War, there are 80,000 unexploded bombs over the border in Laos and every year 300 people are killed and maimed when they accidentally detonate an unexploded device. The nightmare goes on!

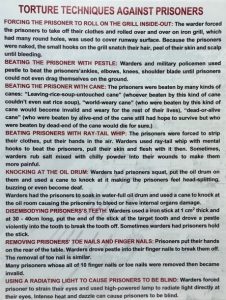

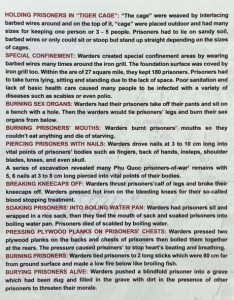

Finally, I visited the annex outside that displayed some of the methods used in dealing with prisoners. The treatment of prisoners was inhumane and the methods used to torture and execute them were barbaric. I’m afraid the French did not come out of it very well for they were using the guillotine up until 1960. The photographs of posters below highlight just how low the perpetrators of these acts became. It makes excruciatingly painful reading. I cannot imagine how the prisoners felt!

I came away feeling angry, angry with the Americans for all of their barbarism. It is not behaviour befitting the most influential nation on earth. I was angry that this had taken place in my lifetime. I was angry that I did not know enough about the war and I was angry that nobody seems to have learned any lessons from what happened in Vietnam, especially the Americans who continue to bully the world. There must have been evil on both sides in the conflict, but the Americans, on the basis of this visit appeared to be incredibly evil. There was only so much I could take and I was pleased when we climbed aboard our air-conditioned bus and it took us away.

After another sumptuous lunch we drove out to Cu Chi to visit the tunnels dug by the Viet Cong during the war. Perhaps, after visiting the tunnels, I might have a more balanced opinion about the war. This complex of tunnels is 300 km long. There were three levels of tunnel, the shallowest being 3 metres below the surface. These were connected by down shafts to tunnels 6 metres below and a lower level of between 8 – 10 metres. There were underground hospitals and schools and many people remained underground for long periods.

After another sumptuous lunch we drove out to Cu Chi to visit the tunnels dug by the Viet Cong during the war. Perhaps, after visiting the tunnels, I might have a more balanced opinion about the war. This complex of tunnels is 300 km long. There were three levels of tunnel, the shallowest being 3 metres below the surface. These were connected by down shafts to tunnels 6 metres below and a lower level of between 8 – 10 metres. There were underground hospitals and schools and many people remained underground for long periods.

On arrival we were taken into the jungle. Once inside, we paused and were asked if we could find the entrance. Scouring the ground, we looked for any give away signs but there were none. What we should have done was start to kick around the dry leaves covering the forest floor. When this was done for us it revealed the tiniest of wooden trap doors, little more than 15 inches by 9 inches. The guide then demonstrated how the Viet Cong disappeared underground and made themselves invisible. Demonstration over, we were invited to have a go. I decided there was no point in me trying as I would not be able to get my bulk nimbly in, or, if I did, out. Others tried, but only the thinner members of the group, and they made it look so easy. You have to remember that the Vietnamese are structurally much smaller than we are, but that does not get away from the fact that they were living in incredibly claustrophobic conditions.

On arrival we were taken into the jungle. Once inside, we paused and were asked if we could find the entrance. Scouring the ground, we looked for any give away signs but there were none. What we should have done was start to kick around the dry leaves covering the forest floor. When this was done for us it revealed the tiniest of wooden trap doors, little more than 15 inches by 9 inches. The guide then demonstrated how the Viet Cong disappeared underground and made themselves invisible. Demonstration over, we were invited to have a go. I decided there was no point in me trying as I would not be able to get my bulk nimbly in, or, if I did, out. Others tried, but only the thinner members of the group, and they made it look so easy. You have to remember that the Vietnamese are structurally much smaller than we are, but that does not get away from the fact that they were living in incredibly claustrophobic conditions.

Moving on through the forest we came across examples of traps they set for patrolling Americans. They were evil and the thought of falling into one or being caught in one sent a chill down the spine. Despite their horror they were ingenious. We saw termite hills that were useful to the Viet Cong for they hid air tubes supplying air to the tunnels below. They were also able to use then as look outs so that they could monitor the movements of the Americans without being seen. When the opportunity arose, they would sneak out from the tunnels, ambush the enemy or attack from behind and then quickly disappear underground.

Moving on through the forest we came across examples of traps they set for patrolling Americans. They were evil and the thought of falling into one or being caught in one sent a chill down the spine. Despite their horror they were ingenious. We saw termite hills that were useful to the Viet Cong for they hid air tubes supplying air to the tunnels below. They were also able to use then as look outs so that they could monitor the movements of the Americans without being seen. When the opportunity arose, they would sneak out from the tunnels, ambush the enemy or attack from behind and then quickly disappear underground.

One intriguing thing we learnt was that in dusty earth it was easy to leave footprints displaying your movements. To confuse the enemy, the Viet Cong made flip flops out of old rubber tyres, but they made the front and back exactly the same. The foot print left behind would not indicate what the direction of travel was, thus adding to the confusion. Brilliant and so simple. In fact, many of the strategies of the Viet Cong were simple and it was a situation of ‘brain’ v ‘brawn’.

One intriguing thing we learnt was that in dusty earth it was easy to leave footprints displaying your movements. To confuse the enemy, the Viet Cong made flip flops out of old rubber tyres, but they made the front and back exactly the same. The foot print left behind would not indicate what the direction of travel was, thus adding to the confusion. Brilliant and so simple. In fact, many of the strategies of the Viet Cong were simple and it was a situation of ‘brain’ v ‘brawn’.

The brawn knew the tunnels were there and did everything they could. They bombed them, but, while a heavy bomb might cause some damage to a tunnel near the surface, they had difficulty penetrating those deeper underground. They tried flooding the tunnels but, because they were on different levels the water always found the lowest levels but, again this had been thought about and the tunnels all had outlets into the river so that any water poured in flowed out again. The Americans tried gassing them, but the tunnel system was so complex, and the ventilation was so effective, it did little harm. The Americans were out thought every time.

The brawn knew the tunnels were there and did everything they could. They bombed them, but, while a heavy bomb might cause some damage to a tunnel near the surface, they had difficulty penetrating those deeper underground. They tried flooding the tunnels but, because they were on different levels the water always found the lowest levels but, again this had been thought about and the tunnels all had outlets into the river so that any water poured in flowed out again. The Americans tried gassing them, but the tunnel system was so complex, and the ventilation was so effective, it did little harm. The Americans were out thought every time.

There are tunnels that have been enlarged so that tourists can go down and get a feel for what it was like. Taking advantage, I crawled around on my hands and knees and still found it very uncomfortable. It was not pleasant, but I appreciated the opportunity to find out what it was like.

There are tunnels that have been enlarged so that tourists can go down and get a feel for what it was like. Taking advantage, I crawled around on my hands and knees and still found it very uncomfortable. It was not pleasant, but I appreciated the opportunity to find out what it was like.

Unlike the visit to the museum, when I emerged angry, when I emerged from the tunnels I found I was full of admiration for the Viet Cong. There was no way they were ever going to beat the Americans in a traditional war, they were up against far too much fire power and dirty tactics. But by taking themselves underground, it was alien to the way the Americans fought, and they were not able to overcome their enemy.

It was a political and military shambles brought about by American paranoia of communism, which, on the battle field, was going nowhere, forcing them to withdraw before they were eventually beaten. Withdrawal was a means to saving face internationally on the world stage, and at home with their own people who had no appetite for war. Personally, I think they came away with an awful lot of egg on their faces and it was well deserved.

That night we decided we would do our own thing for eating. A number of us went to a restaurant on the top floor of the Palace Hotel. We walked there through the throng of New Year revellers enjoying everything that was on offer. The hotel was on the main thoroughfare where the celebrations were taking place, Nguyen Hue. This is normally busy with traffic but for the duration of the Tet Festival it was closed to traffic and brightly decorated with huge beds of flowers and other colourful lights and statues of dogs, as it is to be the Year of the Dog. It was a terrific atmosphere and we were able to look down upon it as we ate our meal.

That night we decided we would do our own thing for eating. A number of us went to a restaurant on the top floor of the Palace Hotel. We walked there through the throng of New Year revellers enjoying everything that was on offer. The hotel was on the main thoroughfare where the celebrations were taking place, Nguyen Hue. This is normally busy with traffic but for the duration of the Tet Festival it was closed to traffic and brightly decorated with huge beds of flowers and other colourful lights and statues of dogs, as it is to be the Year of the Dog. It was a terrific atmosphere and we were able to look down upon it as we ate our meal.

By the time we had finished and were heading back to the hotel, there was no abatement in the street level activity; the crowds still ambled, and despite the hour, there were many children. They had a lot more stamina than me.

On our last full day in Vietnam we left the city and headed out to Ben Tre River, a tributary of the Mekong. There a boat was waiting for us to take us on a cruise, stopping off at various points along the way to give us an insight into delta life.

Despite it only being one of the many channels of the Mekong River, it was still a very significant river and a watery highway for trade. Every so often there were fish traps along the bank, presumably set to catch fish at high tide, although Da Lat was not very confident that they were very efficient and that the fishermen found it hard to change their ways and move away from tradition.

Our first stop was at a brick works. We were led to believe that this was the traditional way of making bricks, and so it was, but it looked very much as if it had not been in action for some time. The kilns were the most interesting part of the visit. These were upturned bottle shaped brick structures that were filled up to the brim with raw bricks. The stacker had to climb out of the chimney at the top to escape. When full, the kiln can hold as many as 12,000 bricks. The process then requires a fire to burn for thirty days in order to harden the bricks. The main fuel for the fire is rice husks. What alerted me initially to the fact that this was now a museum rather than a working brick factory is that there were no huge stockpiles of rice husks, just remnants of where they had been. Nevertheless, it was very interesting and worth the visit.

Our first stop was at a brick works. We were led to believe that this was the traditional way of making bricks, and so it was, but it looked very much as if it had not been in action for some time. The kilns were the most interesting part of the visit. These were upturned bottle shaped brick structures that were filled up to the brim with raw bricks. The stacker had to climb out of the chimney at the top to escape. When full, the kiln can hold as many as 12,000 bricks. The process then requires a fire to burn for thirty days in order to harden the bricks. The main fuel for the fire is rice husks. What alerted me initially to the fact that this was now a museum rather than a working brick factory is that there were no huge stockpiles of rice husks, just remnants of where they had been. Nevertheless, it was very interesting and worth the visit.

Back on the boat we were presented with a coconut each with a cleft cut into it with a straw allowing us to drink the delicious coconut milk. This was the prelude for our next visit to a coconut processing cottage industry. Here a heavily tattooed man deftly cut the coconut out of the husk for us to try. Again, it was delicious. The edible part of the coconut, not eaten by visiting tourists is then made into flavoured coconut sweets using palm sugar. All very sweet and sickly.

Back on the boat we were presented with a coconut each with a cleft cut into it with a straw allowing us to drink the delicious coconut milk. This was the prelude for our next visit to a coconut processing cottage industry. Here a heavily tattooed man deftly cut the coconut out of the husk for us to try. Again, it was delicious. The edible part of the coconut, not eaten by visiting tourists is then made into flavoured coconut sweets using palm sugar. All very sweet and sickly.

Returning to our boat we soon turned into a smaller tributary with palms rising from the muddy waters. Fishermen plied up and down the river in their canoes, casting or pulling their nets, while others stood chest deep in the water.

Leaving our boat, yet again, we visited a weaving workshop. Here two men operating a loom, making a reed mat. As one separated the strings, another fed in a reed using a hook with a rod, which had to be withdrawn before the strings were separated the other way. The speed, dexterity, coordination and team work was to be admired. The man operating the loom had a wooden leg and was either a casualty of the war or a casualty of an encounter with explosives since the war.

Leaving our boat, yet again, we visited a weaving workshop. Here two men operating a loom, making a reed mat. As one separated the strings, another fed in a reed using a hook with a rod, which had to be withdrawn before the strings were separated the other way. The speed, dexterity, coordination and team work was to be admired. The man operating the loom had a wooden leg and was either a casualty of the war or a casualty of an encounter with explosives since the war.

Instead of getting back into the boat, tuk-tuks took us on a journey through the delta community, along narrow tracks to a family run restaurant, which I think was specifically set up for groups like ours. I cannot imagine anybody else would find this place. Like all the meals we ate on this trip, it was excellent, but the centrepiece, a deep-fried fish held on a stand was the best. We just had to dig into it with our forks and take the meat, which fell off the bone easily, and pop it straight into our mouths. While we ate, large butterflies flitted from flower to flower beside us.

Instead of getting back into the boat, tuk-tuks took us on a journey through the delta community, along narrow tracks to a family run restaurant, which I think was specifically set up for groups like ours. I cannot imagine anybody else would find this place. Like all the meals we ate on this trip, it was excellent, but the centrepiece, a deep-fried fish held on a stand was the best. We just had to dig into it with our forks and take the meat, which fell off the bone easily, and pop it straight into our mouths. While we ate, large butterflies flitted from flower to flower beside us.

After the meal we walked a little way along the concreted track through the village. Being in the delta, these paths, had they not been concreted, would have been treacherous in the wet. We walked down to a bridge where there were a number of sampans waiting for us to take us back to our boat. I love this quiet method of travel along these waterways as they give us much greater opportunity to see much more. Unfortunately, the journey was over all too soon.

After the meal we walked a little way along the concreted track through the village. Being in the delta, these paths, had they not been concreted, would have been treacherous in the wet. We walked down to a bridge where there were a number of sampans waiting for us to take us back to our boat. I love this quiet method of travel along these waterways as they give us much greater opportunity to see much more. Unfortunately, the journey was over all too soon.

Once we returned to our bus we had, what should have been a ninety-minute journey back into Ho Chi Minh City. Instead, it turned into a bit of an epic because of traffic returning after the Tet Festival. The dual carriageway was a sea of motorcycles. We were going nowhere fast, until the police closed the lanes to traffic coming towards us so that they could clear some of the queue going towards the city. We saw some interesting sights and continued our search for six on a motorbike.

That evening we ventured out to a restaurant, Hoa Tuc, housed in an old opium factory, for our last meal in Vietnam. It came as a recommendation from OV, Ben Wall, who used to teach in the city. Good choice, thanks, Ben. The festivities in Nguyen Hue were again in full swing when we walked to the restaurant but by the time we were heading back to the hotel, the clear up operation was in full swing. The Tet Festival was over for another year.

That evening we ventured out to a restaurant, Hoa Tuc, housed in an old opium factory, for our last meal in Vietnam. It came as a recommendation from OV, Ben Wall, who used to teach in the city. Good choice, thanks, Ben. The festivities in Nguyen Hue were again in full swing when we walked to the restaurant but by the time we were heading back to the hotel, the clear up operation was in full swing. The Tet Festival was over for another year.

The following morning, I just had time for a stroll around the markets near the hotel before we headed off to the airport for our flight to Siem Reap. Nguyen Hue was back to normal and you would not have known that anything had been taking place there.

Our Vietnam adventure had drawn to a close. It had been an excellent two weeks and we had seen and done so much. I really enjoyed the north and there were aspects of the middle that I enjoyed. I also really enjoyed being in Ho Chi Minh City for the climax of the Tet Festival. The people, everywhere we went were friendly, welcoming and always offering us a smiling face. I cannot imagine not coming back. I am very grateful to Asia Aventura for their excellent organisation and to the guides who, on the whole, gave us added value. Love you, Vietnam!