A guided tour is only as good as the guide.

After an hour and a half’s journey through the countryside of Lesser Poland, we arrived at the expansive, already full car park for Auschwitz Concentration Camp. At the entrance we were met by our guide, Anna, and were quickly whisked through security, collected our radio receivers and head sets and embarked upon a tour of the site where one of the world’s most inhumane atrocities took place.

After an hour and a half’s journey through the countryside of Lesser Poland, we arrived at the expansive, already full car park for Auschwitz Concentration Camp. At the entrance we were met by our guide, Anna, and were quickly whisked through security, collected our radio receivers and head sets and embarked upon a tour of the site where one of the world’s most inhumane atrocities took place.

We paused at the entrance, under the sign, “Arbeit Macht Frei” “Work Sets You Free”. It was a chilling place for us who knew what lay beyond the gate but for the many who came here, initially, might have had some hope. On either side of the gate impenetrable double fences of vicious, electrified barbed wire spread around the whole camp. Every so often a guard house towered above the fence, making it impossible to escape undetected. Beyond, in geometric precision, brick barracks stood, stark and uninviting. Before the war, this had been a Polish military barracks, saving the Germans the necessity to start the camp from scratch.

We paused at the entrance, under the sign, “Arbeit Macht Frei” “Work Sets You Free”. It was a chilling place for us who knew what lay beyond the gate but for the many who came here, initially, might have had some hope. On either side of the gate impenetrable double fences of vicious, electrified barbed wire spread around the whole camp. Every so often a guard house towered above the fence, making it impossible to escape undetected. Beyond, in geometric precision, brick barracks stood, stark and uninviting. Before the war, this had been a Polish military barracks, saving the Germans the necessity to start the camp from scratch.

Passing through the gate the story of Auschwitz unfolded with Anna’s clearly spoken commentary. The fact that we were each wearing headphones meant that we missed nothing and everything she said was as if to you only. She took us into a number of the buildings, building up a picture of the horrors that they faced. In one, it was set out as a dormitory, one side just having straw on the floor, while the other had straw mattresses. There was not a gap between and each room was grossly overcrowded. There were toilets and washing facilities, of sorts, in an adjacent room, but they were not sufficient for such numbers and did not prevent the spread of numerous, often fatal, diseases.

Passing through the gate the story of Auschwitz unfolded with Anna’s clearly spoken commentary. The fact that we were each wearing headphones meant that we missed nothing and everything she said was as if to you only. She took us into a number of the buildings, building up a picture of the horrors that they faced. In one, it was set out as a dormitory, one side just having straw on the floor, while the other had straw mattresses. There was not a gap between and each room was grossly overcrowded. There were toilets and washing facilities, of sorts, in an adjacent room, but they were not sufficient for such numbers and did not prevent the spread of numerous, often fatal, diseases.

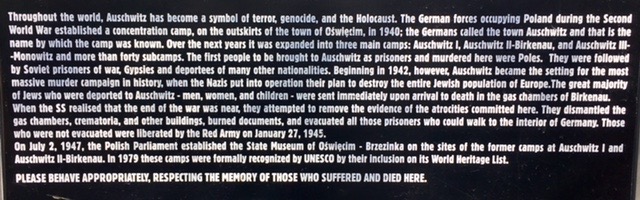

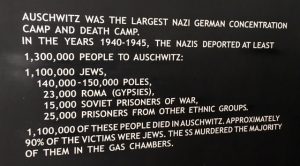

When the Germans had the Jews, and other undesirable sections of society brought here by the train load, they had everything taken from them, their cases, shoes, brushes, pots and pans, glasses, even artificial limbs. Huge piles of these artefacts were displayed in some of the barracks. Seeing these we began to understand the scale of what went on here and specific notices on some of the walls put it into numbers. In total 1.3 million Jews from across Nazi occupied Europe, Polish political prisoners, Roma gypsies, Russian prisoners of war and other ethnic minorities were transported to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. About 1.1 million were murdered. It is an unimaginable figure.

When the Germans had the Jews, and other undesirable sections of society brought here by the train load, they had everything taken from them, their cases, shoes, brushes, pots and pans, glasses, even artificial limbs. Huge piles of these artefacts were displayed in some of the barracks. Seeing these we began to understand the scale of what went on here and specific notices on some of the walls put it into numbers. In total 1.3 million Jews from across Nazi occupied Europe, Polish political prisoners, Roma gypsies, Russian prisoners of war and other ethnic minorities were transported to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. About 1.1 million were murdered. It is an unimaginable figure.

Between blocks 10 and 11 there was an enclosed courtyard where certain prisoners were brought to be shot by firing squad. Initially, a firing squad executed prisoners near the camp at places where gravel had been extracted—the so-called “gravel pits.” From the autumn of 1941 to the autumn of 1943, the majority of executions were carried out in the walled-off yard of block 11, in front of a specially built “Death Wall.”

Between blocks 10 and 11 there was an enclosed courtyard where certain prisoners were brought to be shot by firing squad. Initially, a firing squad executed prisoners near the camp at places where gravel had been extracted—the so-called “gravel pits.” From the autumn of 1941 to the autumn of 1943, the majority of executions were carried out in the walled-off yard of block 11, in front of a specially built “Death Wall.”

The condemned prisoners had to strip naked in block 11, on the ground floor. Any women among them disrobed in separate rooms. The women were then led into the courtyard and shot first. The condemned prisoners were led to the wall in pairs. The SS executioner walked up from behind and shot them in the back of the head with a small-caliber rifle. Designated prisoners threw the corpses onto trucks or carts that delivered them to the crematoria. Many of the people killed in this way were never entered in the camp records. Anna told us that the youngest to die in this way was a nine year old girl.

The condemned prisoners had to strip naked in block 11, on the ground floor. Any women among them disrobed in separate rooms. The women were then led into the courtyard and shot first. The condemned prisoners were led to the wall in pairs. The SS executioner walked up from behind and shot them in the back of the head with a small-caliber rifle. Designated prisoners threw the corpses onto trucks or carts that delivered them to the crematoria. Many of the people killed in this way were never entered in the camp records. Anna told us that the youngest to die in this way was a nine year old girl.

In another block, along the central corridor, there were photographs of prisoners with heads shaved, wearing the striped prison uniform with triangles sewn on to them. The colour of the triangle denoted the kind of prisoner they were – red for political, green for criminal, pink for homosexual and so on. The photographs, three deep along the full length of each wall, showed a gallery of misery. They were nearly all young men and women, deemed fit and able enough to work rather than go straight to the gas chamber. Underneath each picture it gave their name, age, occupation – farmer, baker, carpenter etc., the date they were registered in the camp and the date they died, usually within three months of entry. It was so chilling to look into the vacant eyes of these human beings as we passed down the corridor.

In another block, along the central corridor, there were photographs of prisoners with heads shaved, wearing the striped prison uniform with triangles sewn on to them. The colour of the triangle denoted the kind of prisoner they were – red for political, green for criminal, pink for homosexual and so on. The photographs, three deep along the full length of each wall, showed a gallery of misery. They were nearly all young men and women, deemed fit and able enough to work rather than go straight to the gas chamber. Underneath each picture it gave their name, age, occupation – farmer, baker, carpenter etc., the date they were registered in the camp and the date they died, usually within three months of entry. It was so chilling to look into the vacant eyes of these human beings as we passed down the corridor.

In Block 4 there was a room full of bales of hair taken from women and girls who had their heads shaved upon entry to the camp, or it was retrieved from the corpses before they were cremated. They found 7000kg of matted discoloured hair when the camp was liberated. This is just a fraction of what was taken, the rest having been sent to Bavaria to make into hair cloth. It does not bear thinking about.

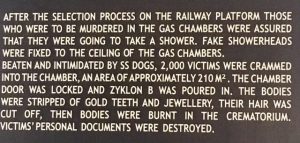

Then we visited the gas chambers where hundreds at a time were herded into a block to have a shower. Before they showered they had to disrobe and were then forced into the chamber. Once they were all in cyanide crystals were dropped in through a number of vents in the ceiling. The vents were then closed and the crystals set about their work of killing everybody in the room. The crystals reacted with oxygen and gradually filled the room with poisonous gas from the floor upwards. As people died, others climbed on their bodies in the vain attempt to get at the less toxic air near the ceiling. There was nothing they could do and no where for them to go. After about half an hour everybody in the chamber was dead and there would be a pyramid of tangled bodies rising to the ceiling. They were then cleared to the crematorium next door and the bodies burnt, leaving nothing but ash to dispose of.

Then we visited the gas chambers where hundreds at a time were herded into a block to have a shower. Before they showered they had to disrobe and were then forced into the chamber. Once they were all in cyanide crystals were dropped in through a number of vents in the ceiling. The vents were then closed and the crystals set about their work of killing everybody in the room. The crystals reacted with oxygen and gradually filled the room with poisonous gas from the floor upwards. As people died, others climbed on their bodies in the vain attempt to get at the less toxic air near the ceiling. There was nothing they could do and no where for them to go. After about half an hour everybody in the chamber was dead and there would be a pyramid of tangled bodies rising to the ceiling. They were then cleared to the crematorium next door and the bodies burnt, leaving nothing but ash to dispose of.

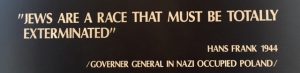

One has to ask the question, how did the guards feel about what they were doing? They had little choice. The German propaganda machine convinced them that they were cleansing the world of all undesirable ethnic groups, the Jews being the most hated. They believed what they were doing was right, and, in any case, they had no alternative than to obey orders or be shot. Some guards, it is known, asked for transfers back to the front, but were denied, being forced to endure years cruelty on an unbelievable scale. How could they sleep at night?

One has to ask the question, how did the guards feel about what they were doing? They had little choice. The German propaganda machine convinced them that they were cleansing the world of all undesirable ethnic groups, the Jews being the most hated. They believed what they were doing was right, and, in any case, they had no alternative than to obey orders or be shot. Some guards, it is known, asked for transfers back to the front, but were denied, being forced to endure years cruelty on an unbelievable scale. How could they sleep at night?

After three hours our tour of Auschwitz 1 came to an end and we were given a ten minute break before we moved on the Birkenau.

After three hours our tour of Auschwitz 1 came to an end and we were given a ten minute break before we moved on the Birkenau.

The Germans built Birkenau from scratch and it spread as far as the eyes could see. Disecting the camp was the railway line that brought train load after train load of prisoners locked into wagons. Many had been so for several days with the ultimate outcome that they travelled in absolute squalor. Many died before they got to the camp.

As they were forced out of the wagons, they were met by a welcoming committee of SS soldiers. The commander was also there to meet them. The prisoners were lined up in front of him and were ordered to file past, a cursory glance and a wave of his hand determined their fate; wave to one side and they would go immediately to the gas chamber, the other the labour camp. The majority were so weak and ill after the journey that they were sent to the gas chambers at the far end of the camp. These were destroyed by the Germans as they fled the camp just before the liberation by the Soviet army in January 1945, in an attempt to cover up the evidence. The destruction hid nothing and the full horrors of the previous five years soon became apparent.

As they were forced out of the wagons, they were met by a welcoming committee of SS soldiers. The commander was also there to meet them. The prisoners were lined up in front of him and were ordered to file past, a cursory glance and a wave of his hand determined their fate; wave to one side and they would go immediately to the gas chamber, the other the labour camp. The majority were so weak and ill after the journey that they were sent to the gas chambers at the far end of the camp. These were destroyed by the Germans as they fled the camp just before the liberation by the Soviet army in January 1945, in an attempt to cover up the evidence. The destruction hid nothing and the full horrors of the previous five years soon became apparent.

As we visited the huts where those spared the gas chamber lived, I couldn’t help feel that those who failed to make the grade for labour might have had the better deal. Their agony was soon over, while those that were forced to work in the most appalling conditions, also lived in the most appalling conditions until the effects of hard labour, starvation and poor sanitary and living conditions killed them. If that did not happen, they would just have easily been sent to the gas chamber once their usefulness ceased.

I wondered how Anna could do this job. Surely, reliving the stories of Auschwitz regularly must have an effect. She told us she guided for three days a week, the rest of the time she works in the archive office. She has a personal reason for being there as some of her family went into Auschwitz and never came out. However gruesome the story is the world needs to be reminded what went on during those dark years. You would hope that we learn from it but looking at other parts of the world where there has been conflict, I’m not sure we all have. Look and Cambodia, Rwanda, the Balkans, they all have gruesome stories to tell.

As gruesome and harrowing the visit had been, it is a visit that must be taken at least once in order to try to understand and come to terms with a very dark episode of the 20th C. Anna, with her clear delivery, her empathy and her passion made it a very special experience.

As gruesome and harrowing the visit had been, it is a visit that must be taken at least once in order to try to understand and come to terms with a very dark episode of the 20th C. Anna, with her clear delivery, her empathy and her passion made it a very special experience.